Summer Bodies Thesis Paper

THESIS Paper for Summer Bodies

Master en Fotografía, Arte y Técnica | Universidad Politécnica de Valencia | June 2023

Acknowledgements

I would like to start by expressing my very great appreciation to my advisor, Diana Blok, for taking the time out of her schedule to guide me through what is uncharted territory for me. Ms. Blok has been generous by providing me with key artistic references, practical exercises, and sharing her own remarkable experience as a portrait photographer in order to help me complete this project and push my own technical abilities.

Thank you to Carrie Lipscomb, art director and one of my closest friends, for the formatting and design (especially the cover) for the final draft of Summer Bodies. To my colleague and former photography student Santos Muñoz for being a sounding board and helping me carry this project across the finish line in the final stage of editing.

Thank you to the following for providing their professional services along the way: Carmencita Film Lab for their film processing, Reprografia BV and la icreativa by PrintMaker for their printing services, and la seiscuatro for taking on the book binding and executing my vision for the final product.

Special thanks to all of my friends and family that voiced their support throughout my entire journey with the Masters program, from the moment I decided to move to Spain all the way to the moment that I typed the last word in this paper - particularly my mother, my grandmother, and my friends Gina Winsky and Kiki Van Son.

Finally this project would not have been possible without the participation, collaboration, and support of all of the people that I photographed. Thank you for your generosity and your vote of confidence.

Abstract

This paper examines the process behind the creation of my first photo book, Summer Bodies. What started off as a way to bring to life my interest in portrait photography through technical and artistic skills I learned through the Masters program at Universitat Politecnica de Valencia, became a personal meditation on democratic ways of seeing, universality, interconnectedness, communication, and the vitality of accidents via photography.

Incorporating an ethos derived from interpretations of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” William Eggleston’s The Democratic Forest, and Moyra Davey’s “Mail Art,” Summer Bodies is a body of work that aims to demonstrate the continue need for a way of seeing that places importance on fleeting connections between strangers and collaboration between photographer and subject. Through reviews of academic articles, exhibitions, and published photobooks, we see the continued influence of Whitman and Eggleston through a current generation of photographers that use the portrait to emphasize communication, connection, and shared value systems. Finally we discuss what photographers and bodies of work most greatly influenced Summer Bodies and how the photo book exists within the context of the social media image.

Keywords: portrait photography, ways of seeing, photo book.

Introduction

I. Preamble

It started off as just an excuse to go to the beach. I would stuff a backpack with my Hasselblad, rolls of film, water for hydrating, a cheap red blanket to lay on the sand, and a book - I was reading Leaves of Grass that summer. Off I went in search of moments when the light hit just right and kept my eyes peeled for people that would make a good picture. The ones with a piercing hundred-yard stare, with the exhibitionist desire to bare it all, or with the generosity of spirit to patiently wait while I set up my camera. What I ultimately found on the coarse beaches in this corner of Spain was that bodies of all shapes, colors, and backgrounds can strip themselves of physical or metaphysical trappings and take their place in the sun, both literally and metaphorically.

Summer Bodies ultimately transformed from a search for interiority and into a journey through something more universal, places where bodies are truly democratized and the identities constructed for us by society cease to exist, even if only for a few seconds. I criss-crossed many beaches and approached people I didn’t know to take their picture. The ones that accepted were then given a pre-stamped postcard so that they could write to me and have the opportunity to seize the narrative of the experience as they saw it. Only a few chose to write back. The ones that did conveyed their own sense of personal journey and shared their well wishes for my own. In a very Whitman-esque plot twist, Summer Bodies became less about portraits of strangers and more about seeing myself through others, in those fleeting seconds when I pressed the shutter and the sunlight, and sea spray and ancient grains of sand all grazed our skin in the exact same way.

II. Challenge & Objectives

Before coming up with a concept, I was confronted with a series of challenges: what message do I, as a photographer, want to share with the world? How can I express it in a manner that is untrodden, uncharted? And above all, why should my work resonate with others? At the close of my second year in the Masters of Photography program at Universitat Politecnica de Valencia (UPV), I found myself, paradoxically, further adrift from resolving these queries. My academic studies had endowed me with new knowledge regarding photography: its masters, theoretical constructs, genres, and its capacity to lay bare the functions of language and communication. I expected that my studies would bring me to a crossroads, where I would be presented with a limited number of paths and where based on what I learned, I could make the right choice. Instead I encountered a labyrinth, confounding my way forward. I was overwhelmed. To create order from chaos, I gradually realized that establishing a specific set of objectives would help hone my realm of interest and confine the creative and research choices that lay ahead. After a lot of deliberation, I came up with the following objectives:

Craft a series of portraits that allowed me to express my own personal perspective and ownable aesthetic choices.

Step outside the boundaries of my own personal personal experience, or at the very least, gaze outward by finding shared threads between my own narrative and that of other people.

Operate creatively within the confines of the resources I had at my disposal.

120mm and 35mm analog film cameras.

Shooting locales that offered an abundance of natural light, considering the absence of portable and dependable lighting apparatuses.

Living and operating within an unfamiliar city, without a network of friends, loved ones, and acquaintances to draw upon as subjects. This meant I would need to venture into public spaces to forge connections with strangers open to the idea of being photographed.

With these objectives in mind, I packed my camera and hopped on my bike to think through my work and unearth my concept in the process.

III. Methodology

When I embarked upon this project in May 2022, I started with preliminary test captures that were shot throughout various sections of Valencia, spanning its streets, parks, port area, and coastlines. Regrettably, these initial trials were largely unsuccessful, as mechanical flaws plagued the process, rendering virtually all negatives initially unusable due to light leaks. The foreboding nature of that initial roll of film proved prophetic, as I encountered many setbacks and challenges intrinsic to analog technology.

Yet, amidst the scars of light leaks, there was one photograph that I was pleased with and became a source of solace—because while it was technically not well made, the natural lighting I captured and the softness conveyed by its subject would establish the aesthetic groundwork for the forthcoming concept. Moreover, in the boundless expanse of Valencia's beaches, where leisure intertwines the lives of locals with those of visitors, I realized there was potential to connect with people from diverse backgrounds and walks of life. The significance of the beach as a primary location is expounded upon in the framework section, and serves as the compass for the book's conceptual message. By electing the beach as my location, an informed decision steeped in the theoretical principles enshrined within Summer Bodies, I propelled myself closer to attaining the first objective of crafting a cohesive body of work exhibiting my own point of view. Ultimately, I traversed the Mediterranean coast beyond Valencia and ventured to the beaches of Murcia and Andalucia in order to meet additional subjects, enriching the narrative tapestry I looked to construct.

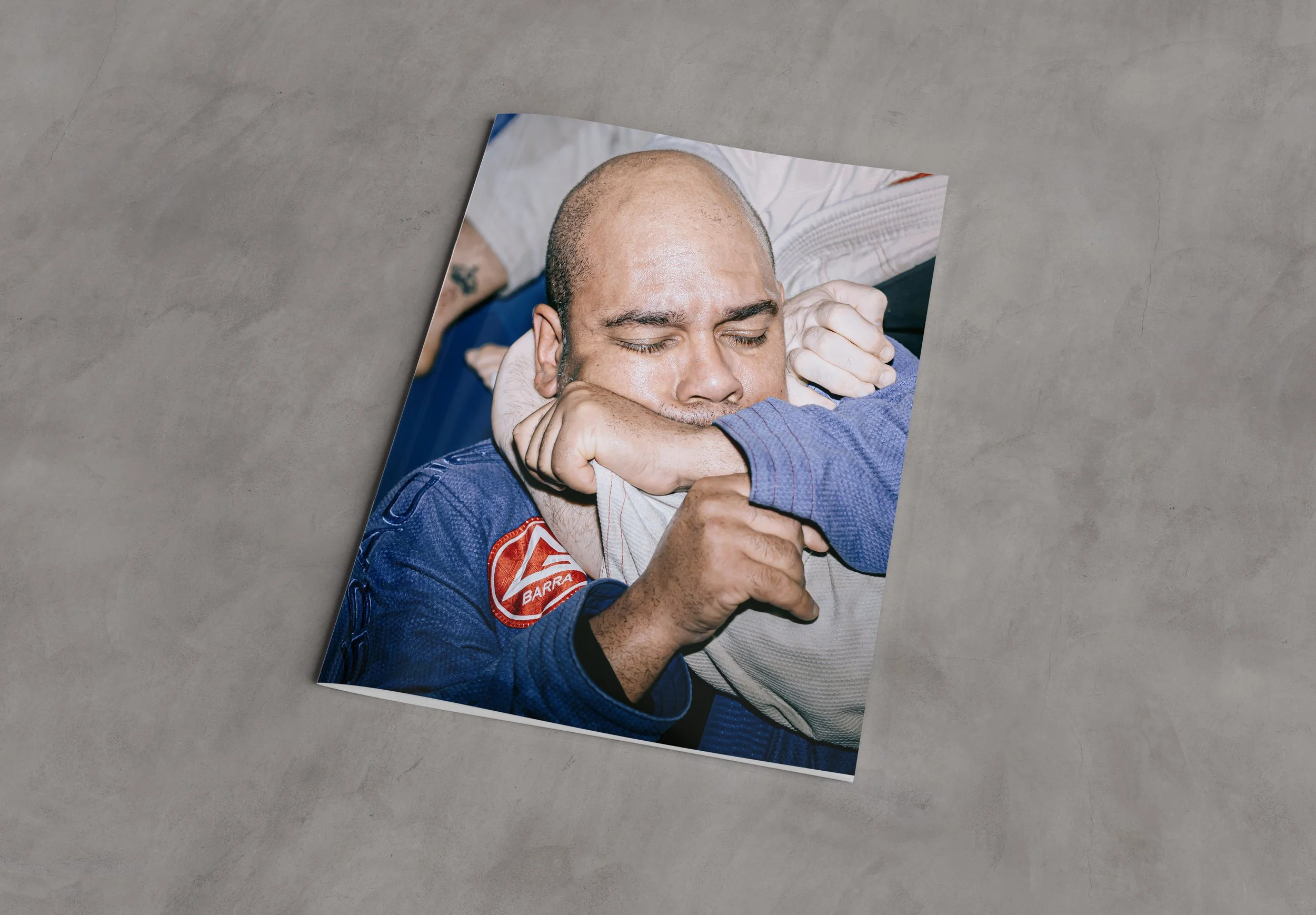

Image 1.1

This was one of the first images captured for this project. From a mostly unusable roll of film, it nevertheless set the tone for Summer Bodies and appears as the first image in the book.

The selection process of the individuals I photographed for Summer Bodies was not steeped in predefined methodology, which is not to say that it was easy. In the act of observing individuals from a distance, deliberating whether to approach them and request their participation in my project, I operated predominantly on instinct and tried to suppress self-doubt that arose from insecurity, shyness, or the fear of rejection. Nonetheless, I attempted to adhere to a rudimentary framework that would, both consciously and unconsciously, validate my choice to cross the threshold of personal space and embark on the "decisive moment":

Do the prevailing lighting conditions align with my aesthetic goals or convey a desirable ambiance?

Does the individual look unoccupied with something or someone else, allowing for an unhurried engagement?

Is there some intangible quality to the individual that beckons me to take their picture?

This rubric, in turn, ensured that my approach to portraiture encapsulated the secondary objective of the project—to transcend my own sense of self and become immersed in the world of another, unearthing the shared threads that intertwine our existence. In an Aperture Conversations lecture promoting his photo book Provincetown, a seminal work that informed and influenced Summer Bodies, Joel Meyerowitz succinctly encapsulated an elevated approach to selecting sitters as follows:

There’s something about the intimacy of selecting another person. And my behavior would be usually to carry my view camera on my shoulder, as if it were a big 35mm camera, and walk up and down the streets or beaches of Cape Cod, and if somebody had a kind of pulse, some kind of a vibration that spoke to me, as if I identified something of myself in the other, I would cross that social distance and say to them “I need to make a portrait of you.” Very simple - My need was my need, and if they were willing to do it we would make a portrait right there wherever we were. I can’t remember anyone ever saying no.

(Joel Meyerowitz, 2019)

Unlike Joel Meyerowitz, I was told “no” by several people (if my memory is correct a total of seven to 10 times, but I did not document this), predominantly during the beginning stages of the project when I was still figuring out a rhythm and a method to my work. However, as the summer progressed and I continued to seek photographs through September 2022, I improved my ability to identify the individuals and the moments that aligned with the parameters outlined by my rubric. Instead of solely relying on aesthetic impulses, I increasingly leaned into an instinct ignited by philosophical undercurrents—an elusive "vibration," as Meyerowitz aptly described. This shift in approach enabled me to navigate beyond the confines of visual ideals and engage with individuals in a way that felt natural, impactful, imperfect, human.

Upon securing the consent of the sitters, each session lasted approximately 10 to 20 minutes. Oftentimes, I arrived prepared with a specific idea regarding the art direction, consciously informed by the artists and photographers I will mention in the references section. These references were thoughtfully selected through the tangential philosophical lineage that they shared with the texts that shaped the conceptual framework of Summer Bodies. On other occasions, sitters contributed their own ideas or suggestions, fostering a collaborative process that unfolded organically, with poses conjured spontaneously. Collaboration and communication emerged as integral themes in the project, as they helped accomplish the second objective: using photographs to tell about commonalities between the sitter and the photographer. I gave each person I photographed a pre-stamped postcard bearing my address, inviting them to communicate their thoughts on any aspect of the experience. I offered various prompts as examples, but usually said something along the lines of - "if this photo becomes famous and is published in magazines and exhibited in museums around the world, what would you want others to know about you?"

Of the more than 20 postcards distributed, I received only three in return. However, each subject was provided with a digital copy of their photograph through WhatsApp or email, subsequently granting their consent for the inclusion of their image within the project. Of the more than 20 pre-stamped and pre-addressed postcards I handed out, these are the only three that I received from people I photographed for the project.

The images that grace the pages of the book were captured exclusively on 120mm or 35mm film, primarily in color, although a few were shot in black and white because that is what I had available at the time. As mentioned earlier, the journey was fraught with an array of obstacles—mechanical glitches due to the cameras' age, and a handful of imperfect frames resulting from human error. Yet, rather than discarding these hiccups, I clung onto them as proof of the authenticity and rawness I sought to convey within the book's narrative and to stay true to the third objective: operate creatively within the confines of the resources I had at my disposal. In the sequencing and editing process, I settled on 50 images, accompanied by the inclusion of two contact sheets, and three postcards that bear witness to the exchange between subject and photographer.

2. Framework

Image 2.1: “The Swimming Hole” by Thomas Eakins (1884-1885). Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Image 2.2: still image of actor Alex Hibbert from the Barry Jenkins film Moonlight (2016). A24.

The passage that opens Summer Bodies comes from a journal entry by Henry David Thoreau dated June 12, 1862. Thoreau recounts what he sees before him:

Boys are bathing in Hubbard’s Bend, playing with a boat (I at the willows). The color of their bodies in the sun at a distance is pleasing, the not often seen flesh-color. What a singular fact for an angel visitant to this earth to carry back in his notebook, that men were forbidden to expose their bodies under the severest penalties! A pale pink, which the sun would soon tan. White men! There are no white men to contrast with the red and the black; they are of such colors as the weaver gives them. (Thoreau, 1862).

The sensuality contained in the first two sentences of this passage is remarkable, and when I first read it my mind conjured an image of Thomas Eakins’s famous painting “The Swimming Hole,” (1884) - beige skin tones against vivid deciduous greens, facilitated by the photographic studies that Eakins took as references for the final product.. However, what most grabbed be about this passage was what followed, in which Thoreau’s sensual rhapsodizing implies a message more implicitly political. It somehow brought me to think back to the Barry Jenkins film Moonlight, an exploration of a young man’s plight to carve out his own sense of self-acceptance, reliance, and resilience against the architecture of society-imposed identities and expectations. “In moonlight, black boys look blue,” one character says, while we see a young Chiron, the film’s protagonist, one night at the beach, momentarily free from parental abuse, bullying, and the everyday dangers of being a black boy in Florida (Iroegbulem, 2019). This may seem like a galaxy-brain connection, unless you consider what Thoreau is actually trying to say. This is best summed up by writer Michael Bronski, who in his book A Queer History of the United States, argues that “Thoreau’s message is that civilization, with its ‘severest penalties,’ is most unnatural. He is arguing that nature not only allows for ‘exposure’ but is a space for racial equality, one wherein even the idea of ‘whiteness’ is exposed as a lie.”

Bronski’s reading of Thoreau’s experience in a Massachusetts river bend laid the first stone in the foundation for the photographic explorations I set out to do on the beaches of Valencia. It pointed me in the direction of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and William Eggleston’s Democratic Forest, the texts that formed the primary themes I sought to explore in Summer Bodies. Against the backdrop of sand dunes, rocky coves, blue skies, and the Mediterranean sea, I challenged myself to photograph strangers and in the process unweave personal understandings of identity, individuality, universality, and the very act of communicating with others in the age of social media and digital alienation.

“Song of Myself

Image 2.1: “Walt Whitman, 1872, Photography by G.F.E. Pearsall. International Center for Photography

Image 2.2: Woodlawn Plantation House, Louisiana, (1941) Photograph by Edward Weston. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

As such, Summer Bodies joins a long list of photographic projects directly inspired by Walt Whitman or guided by the tenements of his writings: from Walker Evans’ documentalist view of the everyman experience (Child, 2011), to Edward Weston’s romantic search of what is quintessentially American (Huntington Library, 2016), to Duane Michal’s interpretation of the sensuality inherent in Whitman’s work (Martin, 1998). Much of that has been attributed to the fact that photographic medium came into being during Whitman’s lifetime, and which he took to like a fish to water. For Whitman, photography represented a new way of seeing and cataloging the world, powerful enough to challenge classicist precedents and forge a new way forward based on the democratic ideals he believed in (Folsom, 1998). One of the many themes that “Song of Myself” explores is the exaltation of the “self” and how it can transcend both space and time (much like photography). The self is each individual, but it is also a universal idea that connects us to one another:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you

(Whitman, 1855, 1)

In all people, I see myself, none more and not one a barley-corn

Less,

And the good or bad I say of myself I say of them.

(Whitman, 1855, 21)

The intricate web woven between the individual and the collective, underscored by its egalitarian essence, seems to have found resonance in the potential that photography held for Whitman. In 1855, when "Song of Myself" was first published, photographic portraits and the ubiquitous "cartes de visites" still predominantly existed within the realm of the privileged classes, but the tides were turning swiftly, propelling these visual artifacts into the realm of mass production. Washington University scholar Paulo M. Loonin contends that Whitman possessed a profound understanding of photography's capacity to democratize the concept of identity, and this visionary outlook permeates Whitman's "political aesthetic" that envelops both the self and the expansive tapestry of society at large (Loonin, 2021). Armed with this insight, my approach to capturing the portraits that would shape the Summer Bodies underwent a transformative shift. I veered away from the pursuit of individuals that would unveil their own interiority before the camera's lens, and instead, I embarked upon a quest to glimpse fragments of myself within others. Keeping this in mind helped me identify strangers on the beach that would be more inclined to say yes to participating in the project. More importantly, it led me to search for an ideal setting in which I could meet and access people from diverse backgrounds, and where privilege or power afforded by our respective identities could be neutralized.

The Democratic Forest

Image 2.3: screen capture from “Rambling through Eggleston's Democratic Forest.” (2021). Alec Soth / Little Brown Mushroom YouTube channel.

Whitman's democratic ethos resonates powerfully within the expansive realm of William Eggleston's color photography, reverberating through the very essence of his seminal project, The Democratic Forest (1989). This profound connection becomes evident not only in the images captured by Eggleston but also in the project's evocative title itself, which “is also a philosophy of democracy: the power of the ordinary, the beauty of contingency, the aim of a universalist view,” (Peiffer 2016). For Eggleston, the “ordinary” constituted the homes, backyards, automobiles, gas stations, and street signs that dominate the everyday near his home of Memphis, Tennessee. In the footsteps of Eggleston's legacy, I embarked on a journey, 33 years later and over 7,500 kilometers away from the world of The Democratic Forest, to the sun-kissed shores of Valencia. It was on these beaches that I discovered the ideal backdrop for my portraits. Within this public domain, accessible to all, people from diverse corners of the globe converge, united in their pursuit of leisure and pleasure. It is within this shared terrain that I aimed to encapsulate the spirit of Summer Bodies, drawing inspiration from Eggleston's illuminating vision, his relentless pursuit of the extraordinary amidst the ordinary. Just as Eggleston declared that he was “at war against the obvious,” I embraced his philosophy as my own, wielding the camera to illustrate a democracy of bodies.

Mail Art

Image 2.4:

The Faithful, (2013). Moyra Davey, greengrassi, London and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

In a metaphorical sense, the fertile soil of Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself" and William Eggleston's The Democratic Forest became the nurturing ground for the ideas and images of Summer Bodies. From this rich foundation emerged profound reflections on photography's role in interpersonal communication. The realization of these outcomes was not predetermined, but rather an organic consequence of the reality of my situation in a new country, embarking on a project that involved capturing strangers on the beach. In this process, I discovered a yearning to get close to others, to engage with them, and to understand them. Perhaps this is a natural pursuit as a Colombian-American living in Spain - for all intents and purposes, an outsider.

Many contemporary photographers who identify as minorities or outsiders have attested to the camera's remarkable power as an icebreaker and a conduit for communication. Tommy Kha, a Vietnamese-American artist, expressed this sentiment in regards to his 2023 monograph, Half-Full, Quarter. Kha frequently speaks about how his affinity for photography stems from its ability to bridge the cultural gap he encountered while growing up in Memphis, Tennessee—Eggleston's hometown—part of a small community of people of Asian heritage (Wolf, S., 2023).

Language is a communal activity…and communal activity is the reason we have slang, dialect, why we have accents. I’m making pictures, so I can find other people that speak in the same way as me. (Kha, 2023)

Tommy Kha's words, although published after the completion of Summer Bodies, strikingly summarize the essence of my process and objective. At the heart of this interpretation of photography as a valuable tool for interpersonal communication lies the integration of postcards in the book. Each subject was given a pre-stamped postcard bearing my address, inviting them to recount their personal experience of being captured by my camera in their own words. These postcards served as a collaborative gesture, upholding the democratic principles championed by Whitman and Eggleston, and seeking to equalize the power dynamics between photographer and subject. In this endeavor, I found inspiration in the "Mail Art" works of Moyra Davey, in which she personally prints, folds, stamps, and mails photographs along with a personal note to her gallerists and friends. This ongoing series has garnered attention for its epistolary significance and its subversion of traditional norms surrounding art display and circulation (Lebovici, 2014). Yet, equally significant is its exploration of themes pertaining to communication and connection, the need to be alone yet also be amongst others - delving into the very essence of human interaction. Summer Bodies therefore looks to explore how the taking of a photograph can facilitate a positive bond between strangers, and how it can also potentially extend this bond beyond the beach where the paths between subject and photographer temporarily cross.

3. References

Image 3.1: “White Bear Lake, MN” (2022). Alec Soth, A Pound of Pictures.

Image 3.2: “Charles Vasa, MN” (2002). Alec Soth, Sleeping By The Mississippi.

Image 3.3: “Melissa” (2005). Alec Soth, Niagara.

Alec Soth

Alec Soth, as a prominent contemporary portrait photographer and a master of the photobook medium, served as a natural point of departure for my exploration. His work is often guided by the values espoused by Walt Whitman, and he is arguably the most acclaimed contemporary photographic embodiment of those principles. Soth directly references Whitman throughout his oeuvre, such as in his retrospective Gathered Leaves (2015) which is titled after a line from "Song of Myself," and his most recent book Pound of Pictures (2022), further establishing his connection to the poet's legacy (Soth, 2015; Pantazi, 2016). Soth's photographs not only capture the sitters themselves but also reveal the dynamic interplay between them and the photographer. This narrative of interaction intrigued me, leading me to gravitate towards his portrait of a young bride from Niagara (2002). The "business casual" pose and enigmatic Mona Lisa-like expression suggest a stillness born from the patience, trust, and rapport developed between Soth and his subject. This deliberate approach to posing is evident in many of Soth's other portraits, including the often-reproduced "Charles Vassa, Minnesota '' from Sleeping By The Mississippi. It is a technique embraced by other artists and one that I consciously incorporated into my own work. In A Pound of Pictures, Soth embarks on a cross-country road trip, employing a stream-of-consciousness that infuses rhythm and narrative into the book format (Hustvedt, 2022). In A Pound of Pictures, an image of a list of potential photographic subjects taped to Soth’s steering wheel particularly stood out for how it delineated his mission and his destination. This evocation of a journey is directly alluded to in Summer Bodies through a pair of images taken during my own travels, as I ventured beyond Valencia to explore beaches in other locations.

Image 3.4: “Naples, Texas” (2022). Alec Soth, A Pound of Pictures.

Image 3.5: “Books in an open road” (2023) from Summer Bodies.

Joel Meyerowitz

The work that served as the most direct reference for Summer Bodies was Provincetown by Joel Meyerowitz. Meyerowitz, an intriguing figure, has left an indelible mark on the genre of street photography since his foray into the medium in the early 1960s. He has previously stated being inspired by Robert Frank's evocative melancholy, but over time Meyerowitz developed a style that exudes ebullience, vibrancy, and grace (Cole, 2018). Alongside the likes of William Eggleston and Stephen Shore, he was among the vanguard of photographers who embraced color photography in the realm of fine art (Hinson, 1992).

Color is a language I work in because it is a more direct way to my feelings. Because it has liberated me from the photographic incident. Because through its incredibly descriptive voice I can find my own. I find new interests in subjects that were unavailable to me before…the wide spectrum of light reaches and triggers a lifetime of collected memory.

(Meyerowitz, 1992).

Provincetown, from a collection captured in the late 1970s and early 1980s, breathes with an emotional immediacy derived from his masterful grasp of color technique and the deliberate, unhurried use of a 8x10 camera for the purposes of street photography. My attraction to this body of work stemmed from multiple factors, the foremost being my familiarity with the LGBTQ+-friendly artistic haven that Provincetown represents. Growing up in nearby Connecticut and spending summers in Provincetown with friends and family, I recognized it as an American parallel to the Spanish beaches of Summer Bodies. Both locales exert a magnetic pull, offering leisure and refuge to individuals from diverse backgrounds and experiences. In Provincetown, Meyerowitz found a sanctuary for those whose identities were marginalized by the dominant culture. In Summer Bodies, the coastal landscapes facilitate liberation from the confines of fixed identities themselves. In both instances, we were drawn to the generosity of spirit of the people we came across in our respective beachside democratic forests. Provincetown's influence on my work proved instrumental in comprehending how to utilize the beach as a tableau that frames the delicate interplay between subject and photographer. It also provided cues on leveraging each sitter's unique gestures and body language, capturing the nuances that convey their individuality.

Image 3.6: “Caroline” (1983). Image 3.7: “Denise” (1985). Image 3.8: “Henri” (1981).

Image 3.9: “Genevieve” (1982). All images from Joel Meyerowitz Provincetown (2019).

Rineke Dijkstra

Alec Soth and Joel Meyerowitz have both talked at length about their portrait-making processes, and how it helps them engage with the world as a meditative act. Their reflections, documented through various channels such as teaching, interviews, and even Soth's active presence on social media, emphasize the transformative potential inherent in photographing others (Pantall, 2021). Rineke Dijkstra, another photographer who exemplifies this ethos, delves into the depths of identity, vulnerability, and the intricate dynamics between photographer and subject. Dijkstra's "Beach Portraits" project, realized during the mid-1990s, showcases her deliberate selection of subjects, bathed in exquisite lighting and captured through her large format camera. Each photograph invites viewers to explore the nuances of character as seen through Dijkstra's discerning lens. While her work undoubtedly draws from an ethnographic lineage rooted in the traditions of August Sander and Thomas Ruff (Stallabrass, 2007), it is Dijkstra's emphasis on expressiveness and her blending of various genre techniques, such as fashion and documentary, into a singular portrait that resonated deeply with me. "Beach Portraits," alongside Meyerowitz's Provincetown and various works of Alec Soth, served as primary influences, inspiring me to embrace a street photography approach that transcends the confines of identity, seeking instead the common ground that unites the bodies standing before my camera. Through the lens of these photographers, one can witness the profound impact of serendipitous encounters and the richness one can find in photographing fleeting moments.

Image 3.10: “De Panne, Belgium,” (1992). Rineke Dijkstra, Tate Museum.

Wolfgang Tillmans & Moyra Davey

To delve further into the possibility of photography as a conduit for connection, I turned to the works of other artists who have grappled with this same subject. Among them, Wolfgang Tillmans is a prominent figure, actively exploring the yearning for connection, the intrinsic social nature of photography, and how purposeful aesthetics and stylistic choices are in their own right, a value system that can be shared with others (Hägglund, 2019). Tillmans is a convener of intimacy, capturing in his static images the essence of the collective, the communal, and the democratic. His body of work disrupts hierarchies that dictate the order of things, with no single image exerting importance over another (Hägglund, 2019). Nightclubs, embracing couples, warehouses, protests, and parades are interspersed with astronomical vistas and seascapes in his exhibitions and books, underscoring the transformative potential of physical connection. Through his frequent portrayal of the unclothed human body, Tillmans offers forthrightness without always veering into eroticism, channeling instead a yearning for solidarity (Deitcher, D & Tillmans, W., 2019), values that I looked to communicate through the clothed and unclothed portraits of Summer Bodies. In the process of sequencing and editing my book, I found guidance in Tillmans's Four Books, a compilation of his past works meticulously designed and curated by the artist himself for Taschen. This exploration illuminated the significance of perceiving the collection of photographs as a unified entity, eschewing preciousness or rules that tell us what makes a photograph “successful” or not, or undue emphasis on any individual component. Moyra Davey aptly characterized Tillmans's images as "flares and light leaks, giant swaths of color spilling across the paper like thrown paint. They are nothing if not a testament to the possibilities of accident" (Davey, 2007).

Image 3.11: “Christopher Street Pier,” (1995). Image 3.12: “Fragile Waves” (2016)

Image 3.13: “Smokin’ Jo” (1995). Wolfgang Tillmans, Four Books.

This passage comes from Davey's essay "Notes on Photography and Accident," wherein she delves into the notion of accident as the life force of photography, drawing inspiration from various artists and the writings of Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, and Walter Benjamin. Davey's insights provided me with a sense of liberation and solace as I immersed myself in the creation of Summer Bodies, navigating through moments of frustration like rejections from subjects, camera malfunctions, and images that failed to materialize as initially envisioned. This sentiment is encapsulated in the concluding section of the book, where I included an email exchange with a willing participant whose photographs ultimately did not come to fruition. As mentioned earlier, Moyra Davey's ongoing "Mail Art" series also served as a wellspring of inspiration, prompting me to foster collaboration and exchange with my subjects through epistolary exercises, manifested in the form of the postcards I distributed and requested each sitter to contribute to.

Diane Arbus

For this project, I purposefully referenced artists working in the here and now (with the exception of Joel Meyerowitz) so as to illustrate how democratic aesthetic ideals of Walt Whitman and William Eggleston work through a contemporary lens. However, each of them follow in the lineage of previous masters, particularly that of Diane Arbus. Her influence, from the way she worked with sitters, to the people she chose to photograph, is inescapable. While I use a variety of formats in Summer Bodies, I primarily worked in square aspect ratio to allude to the style that she pioneered and the legacy that she has passed on to the works I have referenced.

Image 3.14: “A Family One Evening In Nudist Camp,” (1965). Image 3.15: “Young Woman with a Coat On Her Bed,” (1968). Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (1995).

Project Characteristics

Subjects

I have talked about Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” William Eggleston’s The Democratic Forest, Moyra Davey’s “Mail Art” and several photographers inspired me to explore the themes of democratic ways of seeing, universality, interconnectedness, communication, and the vitality of accidents via photography. Now I would like to take the time to discuss how I executed these themes through the photographs and the pages of Summer Bodies.

I conceived the work first and foremost as a portrait series, given my interest in that genre. As discussed in Section II (Challenges and Objectives), I took a street photography approach at the beach to overcome the challenge of not having a social circle in Valencia that I could call upon and ask to participate. The beaches became my own “democratic forest” where I could use my camera to connect with other people, to showcase them through the commonalities they shared with others and myself. Through my lens, I gravitated greatly to corporeal forms and skin, as evidenced by the title of the book itself. Most of my subjects are in some state of undress, which is to be expected given the beach setting. Some are in bathing suits, others in shorts and t-shirts, quite a few are completely nude. This was purposeful in conveying the theme of universality - the beach as a place where all bodies are welcomed and can take their place in the sun (literally and figuratively). It also represents the shedding of privileges inherent to any one identity that can happen at the beach, as was observed by Henry David Thoreau through the quote that opens the book. That is to say, the nude woman on page 42 and the nude woman on page 49 both hold equal importance and gravitas on the beaches of Valencia and the pages of Summer Bodies.

Bodies and the beach are the principal photographic subject matter in Summer Bodies, but many readers may pick up on another recurring motif - the red cloth. This was an inexpensive blanket that I bought at a local bazaar and brought with me each time I would go to the beach. I would offer the blanket to sitters that agreed to participate in the project but did not feel comfortable showing everything, whether it was their face, genitals, or identity. The red cloth came to represent the interconnectedness that I wanted to communicate through Summer Bodies, the shared or communal act that summer at the beach represents and how it equalizes the human experience for people from diverse backgrounds. The red cloth is literally a connective thread that weaves its way from one stranger to another (pages 19, 21, 27, 45, 50, 83, 101). In addition to its supporting role in these images, I also wanted to valorize this cheap red cloth and its potential to represent something more, a nod to the “power of the ordinary” exemplified by William Eggleston’s The Democratic Forest. The red cloth is also a more figurative method of illustrating the use of photography to communicate with sitters and with audiences with shared values. The postcards are the most concrete realization of this theme. Not only do they serve to infuse a collaborative spirit to Summer Bodies, but they also serve to propel the narration forward, with each of the three postcards included acting as the beginning of sections within the book.

Summer Bodies aims to operate as both a portrait study and a biographical piece of work, documenting other people’s bodies through my own experience in meeting and bonding with strangers. I don’t appear in any of the photographs, but I did want to offer fragments of myself to the sitters and to the book, a sentiment exemplified by this passage from On Photography: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt,” (Sontag, 15-16). My way of doing it was by the deeply-personal inclusion of my dog Noe, who appears alongside one of the sitters on page 21 and elsewhere on pages 59 and 91, enjoying his time at the beach.

Publishing

In putting together the sequencing and editing of the book, the final result comprises 50 images, two contact sheets of errors, and three postcards. The book dummy/maquette was designed in A5-size, as I wanted a book style that felt portable, journalistic and lived-in, eschewing fine art formats that feel antithetical to the themes of the book. I chose a matte recycled paper coupled with string binding so that it feels rustic and casual. One should not be precious when picking up and thumbing through Summer Bodies. One should feel close to it, write in it as they would in a journal, or even take it to the beach. My intention is to submit Summer Bodies to several independent book publishers for consideration for a small-print run.

Conclusion

About the Title

The rise of the term "summer body" in popular culture can be attributed to the pervasive influence of social media. With over 4 million Instagram posts and 1.7 billion TikTok views under the #summerbody hashtag, the online landscape is flooded with images, videos, and articles that promote an idealized notion of a summer body—slim, toned, with sculpted abs, bronzed skin, and an air of vitality. Countless workout tips and routines promise to help individuals achieve the coveted summer body, while influencers and content creators share their daily dietary habits through “What I Eat In A Day” videos on TikTok. The mantra "summer bodies are made in the winter" is reposted so many times that it feels like an age-old adage.

The title Summer Bodies came to me when watching an episode of the US reality show Vanderpump Rules, when the slim, blonde, traditionally attractive Lauren “Lala” Kent admonished the less slim Katie Maloney for “not working on their summer body.” The implication was clear to viewers, including myself—Maloney was deemed inadequate for displaying her image on Instagram and reaping the social validation that accompanies it. However, the conversation around "Summer Body" has become more nuanced and complex in recent years, thanks to the Body Positivity movement. We have become increasingly aware of how social media pressures can negatively impact individuals' self-image and mental well-being.

The Elephant in the Room:

I have talked about my literary and photographic inspirations when it came to the conceptualization and creation of Summer Bodies, but I would be remiss if I did not admit that social media was the elephant in the room. However, I do not perceive it as a direct response to body image discussions on social platforms but rather, it is my attempt to challenge the dominant paradigms of a digital existence.

Having spent more than a decade working in digital marketing, I worked to create ads for multinational corporations, meticulously aligning their business objectives with those of tech companies like Meta and Google, whose mission is to maximize the amount of time people spend on their platforms so they can charge more for advertisements. It may be cynical, but my opinion as formulated through my line of work is that tech juggernauts cloak their endeavors under the rhetoric of connectivity, yet beneath their façade lies their true intention, one meticulously engineered to serve their commercial interests. This in turn has the power to shape how its users see the world, and how the photographic image is used for expression and communication. I felt compelled to subvert this.

In my quest for an alternative framework, I found solace in Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself" and William Eggleston's The Democratic Forest. These works, unshackled from the aesthetic rules imposed by algorithmic programming, provided me with a liberating foundation. They also underscored the significance of genuine human communication and illuminated how photography can serve as a potent tool for such endeavors. “It’s a fitting context for…and takes on new meaning at a time when social media and smartphones have made us more connected and divided than ever before, ” (Pantazi, 2016).

Embracing the medium of the photo book, I embarked on a path that forced me to consider the interplay of each image, weaving them into a cohesive narrative that would submerge readers in an alternate experience to the lull of a phone screen. This conscious choice was a deliberate act of resistance against the sway exerted by social media over image-making.

Summer Bodies, in no way aspiring to be revolutionary or groundbreaking, acknowledges its modest place within the pantheon of artistic achievements. It stands humbly in the shadows of Alec Soth, Joel Meyerowitz, Moyra Davey, and the countless luminaries whose brilliance ignited its inception. Yet, I hold an earnest hope that this modest endeavor can, to some extent, advocate for the power of photography and resonate with others that feel the same way—a force capable of forging genuine connections and transcending the confines of an algorithmic world.