Post-Identity Politics: Prescribed and Owned Narratives in Contemporary Photography

Post-Identity Politics:

Prescribed and Owned Narratives in Contemporary Photography

Photography has always been a tool used in the examination of human identity, but it was not until the last half century that, as curator and writer Liz Wells states: “people were encouraged to visualize aspects of their own experience, thus challenging marginalization or stereotypes. Working class people, women, gays and people of color were empowered by taking control of the media to imagine their own lives,” (Wells 2003: 376).

Today's “identity art” adheres to the principles of intersectionality – a term first proposed in 1989 by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in her legal forum Demarginalizing The Intersection of Race and Sex. In her words, intersectionality is an “analytical sensibility, a way of thinking about identity and its relationship with power. Originally articulated on behalf of black women, the term brought to light the invisibility of many constituents within groups that claim them as members but often do not represent them” (Crenshaw 2015).

Intersectionality explains how factors such as race, gender, class, and sexuality converge to form identities through which we not only experience oppression, but can also find strength (University of Washington, 2021). As proof of the importance that discourses on intersectionality and identity politics have acquired in contemporary art, we can refer to the winter 2021 issue of Aperture magazine titled "Latinx," a sample of the diversity and plurality of the Latin American experience . Notable works include “Adelante,” a moving series of family portraits by young Salvadoran-American Steven Molina Contreras, the collage series “Woman-Landscape #4 (On Opacity)” by the Dominican-American Joiri Minaya, and “Bridge of Mirrors” by Génesis Báez, a meditation on the women of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Each of these works, and the “Latinx” theme as a whole, represent the current artistic vanguard that celebrates that which has the power to positively represent and take responsibility for an entire community, culture, or identity (Antonio 2018: 168-170 ).

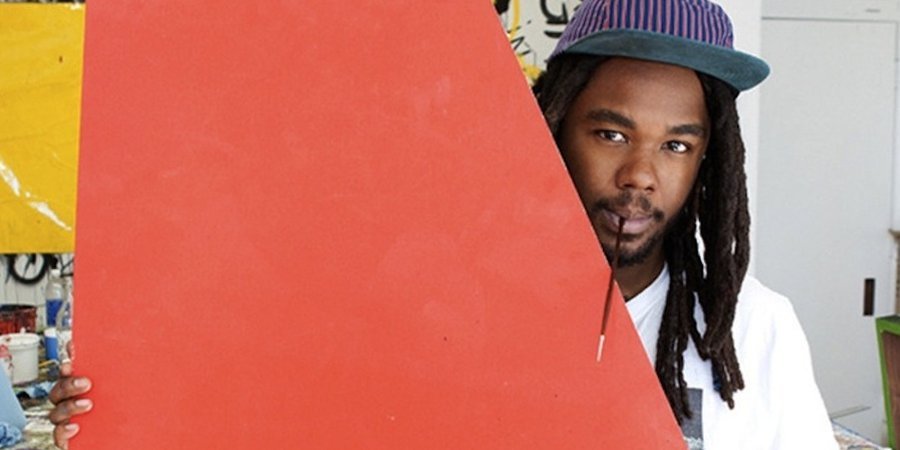

Museums, academia, and publishers have come to recognize the importance of having different perspectives told by the voices that represent them. But how much of this is driven by artists who want to represent their communities and how much is driven by gatekeepers who seek to diversify the art world through the classification and categorization of its creators? Los Angeles artist Devin Troy Strother has been recognized for his iconoclastic and darkly humorous work, exhibited at art institutions such as LACMA and the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. However, in a 2015 interview with Vice, he was vocal about the narratives that the art world has routinely prescribed for him. “I really don't want to talk about being black. But I'm going to have to talk about it. It's like this weird escapist thing where you're trying to do work that's not about identity, but doing work that's not about identity is also about identity.”

Strother never rejects or denies his identity as an African American male in his art; the titles of his paintings often make direct reference to this reality. However, he is frustrated that the other layers of his identity are never recognized. Although rooted in progressivism in most of its issues, when it comes to its views on identity, the art world has not caught up with the post-structuralist view of identity, one that specifies that identity it is dynamic, ever changing in space and time, and not entirely determined by the individual (Norton 2000). According to Bryan Smith of Mejiro University, the maneuvering for social positioning that occurs between groups and individuals and their associated power dynamics also play an equally important role in determining our identity: “The general principle is that the individual/s with more power within a given situation, have more say in the matter,” (Smith 2016: 253-263).

That is to say, the identity that we claim is surpassed by the identity that the group gives us. In the case of artists and photographers, including a commercially successful one like Devin Troy Strother, the power to define one's identity rests with curators, gallerists, publishers, critics, and the public-at-large.

As a student of the Master in Photography at the Universidad Politecnica de Valencia (UPV), questions about my identity are always on my mind. What is my unique POV? What can I say that will help me stand out and stay relevant? How do I define myself in the photographic community? Each teacher has been incredibly helpful in sharing their own unique point of view. One in particular, a celebrated art critic and director of one of the world's leading art institutions, offered this advice: “Look to your Colombian identity for inspiration and theme. There are important stories from Colombia that Colombians must tell and share with the world. Some of the most exciting art today comes from Latin America."

I am very grateful for this genuine, intelligent, and realistic advice. I didn't back down by adding that although I was born in Colombia, I have spent practically my entire life in the United States. When others ask me about my identity, out of habit I share that I am "Colombian-American." This intersectional identity could potentially put me in the scope of Aperture 's next "Latinx" issue . And yet, the truth is that I don't feel particularly Colombian or American. Sometimes, I identify more with that empty space occupied by the hyphen that connects my two nationalities, a kind of demilitarized zone that is not owned or claimed by either of them. When I travel to Colombia, Colombians rarely recognize me as one of them, as I lack the clothing, speech, or body language coded by a lifetime of lived experience as a Colombian. I also lack firsthand knowledge of the violence and conflicts that have plagued Colombian society since the 1940s, at least in the eyes of most Americans and Europeans. Meanwhile, growing up in the United States came with a lot of questions from students and teachers about where my name came from, where my parents were from, where I was from. The way I speak English, the way I dress, and the places I lived in didn't quite fit Latino stereotypes either. In short, the way I personally see my identity is that it is not the sum, difference or product of my two nationalities. It's a space of unresolved tension and suspense, further complicated by the fact that I now live in Spain, which offers its own version of my identity based on its own cultural context.

This, of course, echoes Strother's observation that giving up one's assigned identity becomes one's own identity, a way the outside world defines one as an individual. And while the art establishment has adapted many post-structuralist systems and theories into its mainstream, it has yet to catch up with the post-structuralist view of identity as something that evolves and transforms with each new social interaction (Smith 2016: 263 -273). In her guest editor's note on “Latinx”, Pilar Tomkins Rivas offers an understanding of this by stating that “the processes of visibility and belonging are not fixed but are constantly evolving”. As such, I hope the art world can evolve into something like a post-identity era , where artists are free to be whoever they want to be, but also free to be nothing at all.

Bibliography

Antonio, S. (2018). “Identity, Originality, Multiculturalism and Accountability in 21st Century Art.” Quadranti – Rivista Internazionale di Filosofia Contemporanea. 6 (1), 168-170.

Crenshaw, K. (2015, September 24). “Opinion | Why intersectionality can’t wait.” The Washington Post. Retrieved July 10, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2015/09/24/why-intersectionality-cant-wait/

Norton, B., (2000). Identity and Language Learning. Harlow Englang: Pearson Education Ltd.

Sokol , Z. (2015, January 12). Artist Devin Troy Strother doesn't want to talk about being black. VICE. Retrieved July 5, 2022, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/av4x88/artist-devin-troy-strother-doesnt-want-to-talk-about-being-black-111

Smith, B., (2016). “Poststructuralist Theory of Identity: Its Framework and Implications for Language Learning.” Mejiro University Humanities Research. 12, 253-263.

Tomkins Rivera, P (2021). You Belong Here: Guest Editor Pilar Tomkins Rivera on photographs that collectively chart the history and future of Latinx culture. Aperture, Winter 2021, 21-25.

Wells, L. (2003). The Photography Reader. In Image and Identity (1st ed., p. 376). Routledge.

The Intersectional Approach to Art and Beyond. (2021). Manifold at the University of Washington. Retrieved July 5, 2022, from https://uw.manifoldapp.org/read/keyword-intersectionality-michelle-leca/section/34a96a82-01ec-4b34-99d4-267f829dbec6