THE ART OF WORK: A Photographic History of the Male Body

The Art of Work:

A Photographic History of the Male Body

Historically, the representation of the male body has posed great challenges for the predominantly white, male, heterosexual gaze of the Western photographic tradition. The male gaze seeks submission from its subject for its own scopophilic enjoyment (Berger, 2008; Mulvey, 1989), as demonstrated by its innumerable depictions of the female body. By capturing the male body, the male gaze is forced into a representational dissonant state that forces it to question what a man’s body is supposed to look like, the audience it is meant for, and what it all says about masculinity. In an attempt to address these questions, photography has historically looked at the male body in two contexts. The first is the male body as a work of art, in which it is mined for its artistic potential and aesthetic ideals. The second is as an instrument of labor, in which the male body becomes artistic personification: the art of work. Beginning in the 1970’s, a new generation of photographers began to integrate and subsequently disintegrate these two themes.

In The Beginning

Pictorialism, considered to be photography’s first artistic movement, was primarily concerned with elevating the medium to the pantheon of fine arts. As such, it frequently took inspiration in technique and subject matter from contemporary artists. However, they looked to the Ancient Greeks for guidance in how to photograph the male body, from whom they borrowed two figural forms.

The kouros, a classic figural type that is trim, youthful, and noble, takes center-stage in the work of Wilhelm von Gloeden, one of the first photographers to specialize in the male nude, as well as Julia Cameron Mitchell, F. Holland Day, and Imogen Cunningham. For these photographers, having a direct dialogue with Classicist figurative forms was a way of making a case for photography’s artistic integrity at a time when it was in doubt (Teicher, 2016). The kouros made it acceptable to photograph the male body for its aesthetic value - beauty for beauty’s sake.

The strongman also helped reinforce aesthetic ideals of masculinity. Physique photography, featuring contemporary famous athletes such as Eugene Sandow and Charles Atlas harkened back to Ancient Greek heroic nudes, in which male bodies are flexed and entangled in combat, confirming their dominance over their foes in both sport and war. The strongman as the preeminent icon of a physical kind of masculinity, became entrenched through its depiction in photography (Conrad, 2021).

The Industrial Age invention of sports as leisure for the ascending middle class helped birth physique magazines in which men with the economic means could access photographs of the strongman physique. In (Re)presenting Masculinities: Introduction to Men's Bodies, Judith Still writes that these photographs “intimate to their readers that they are not showing working men - whose muscle development through labor would most likely to be imbalanced. Instead the photographs show the idealized perfected muscled nude body which has been constructed by professional exercise,” (Still, 2003).

The strongman, and the invisible lines that demarcated socioeconomic and cultural distinctions by body type, set the stage for the next evolution of male bodies and masculinity in the realm of photography.

Modernism (1930’s - 1960’s)

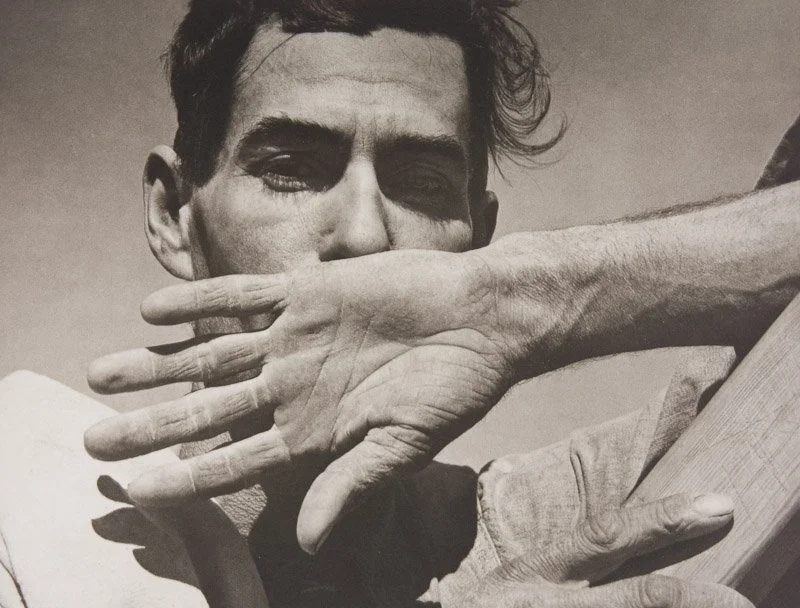

The modernist era saw the documentary genre propelled to the vanguard of photography, thanks to the work of the Farm Service Agency (FSA) photographers of the 1930’s, the Paris Humanists of the 1950’s, among others. Their influence is far reaching, including how they coded the visual representation of the male body.

Pioneers of this field include the surrealist fashion photographer George Platt Lynne and the mystic, spiritual Minor White. However, because of the social mores of the time, their photographs of the male nude were not publicly seen. Attitudes toward the male body in the modernist era is perhaps best summed up by how they appeared in the apotheosis of humanistic photography, MoMA’s The Family of Man exhibition (1955) (Pardo, 2019).

The Family of Man views masculinity through the lens of the “art of work,” celebrating its strength in physical labor as a unifying force for humankind. One chapter features undressed American fisherman, African rowers, and Chinese chain gangs, summarized with an afterword from Hindu scripture: “If I did not work, these worlds would perish,” (Steichen & Sandburg, 1955).

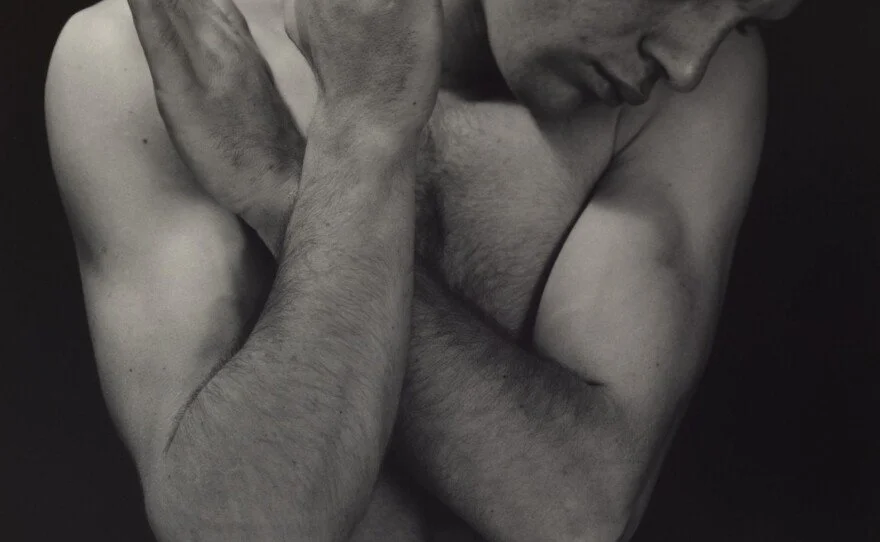

One image does manage to stray from “the art of work” ethos. In Jakob Tuggener’s “Schiffsnieter” (1947), the interlocking muscular arms of two men can be interpreted as teamwork by some viewers, but it can also be read as a sensual admiration of the male form. Tuggener’s image is a throwback to the strongman aesthetic of an earlier photographic age, but it is also a harbinger of things to come.

The Postmodern Age

The 1970’s brought radical shifts to photography as it finally entered the art world. Dianora Niccolini’s The Male Nude (1975) is considered by some to be the first public exhibition of its kind.8 Arguably, the big bang of the male nude was the arrival of Robert Mapplethorpe. Never before had a renowned photographer exalted the aesthetic of the male body in a manner that was so defiant of the heterosexual male gaze. The power of Mapplethorpe’s images lay in the fact that, as stated by Robert Asen, they are shown “simultaneously as formal objects of appreciation and erotic objects of desire” (Asen, 1998).

The same time period saw the ascent of conceptualism and the artists of the “Pictures Generation,” who took a look at the hyper-visual culture in which they were born into and challenged the socially manufactured constraints of gender and identity (Eklund, 2004). Richard Prince’s “Untitled (Cowboy)” (1989) is a photograph of a photograph of the ubiquitous Marlboro cowboy, a symbol of rugged American masculinity. While the Family of Man’s “art of work” images reinforced a socially-accepted form of masculinity, Prince’s image subverts by revealing how certain icons of masculinity are actually manufactured products.

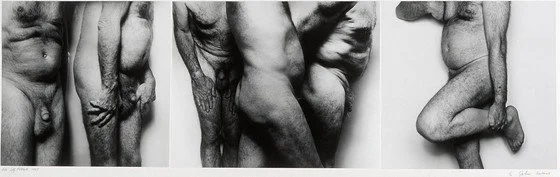

The aesthetic ideals of the male body are questioned in “Self-Portrait Three Times” (1987). Here, John Coplans aims the camera at his own aging, hairy body in a Three-Graces composition, something that would have likely horrified the Ancient Greeks and the Pictorialists. For Coplans, nude self portraits were a way to rid himself of the “usual signifiers of identity and culture…to rediscover an identity out of the composite person he had become in his years as a painter, critic, curator, magazine editor and museum curator” (Leffingwell, 2003). Through his oeuvre, Coplans manages to decrypt and destroy the codes of the male body as a work of art or as the art of work.

Today

All of the photographers I have mentioned so far have one thing in common - they are all white. When it comes to our current era, masculinity is defined by examining its multitudes. The 2020 exhibition Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography held at London’s Barbican Gallery indicates this in its very title. In the exhibit’s “Reclaiming The Black Body” chapter, curator Alona Pardo states that the work of black artists such as Deanna Lawson, Samuel Fosso, and Hank Willis Thomas demonstrate “how Black masculinity challenges the status quo…[and] often ‘idealized (in their physical beauty) and pathologized by the culture (as symbols of violence or fear),” (Del Val, 2020).

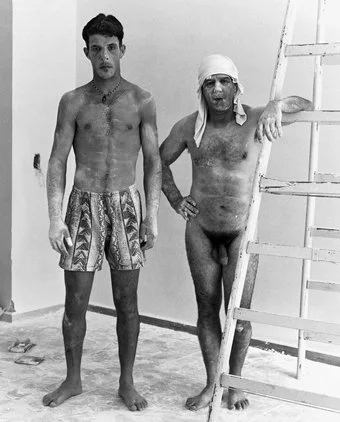

Ultimately, the deconstruction of masculinity in the present day is most successful when viewed from an individual, localist perspective. The work of the late Ren Hang has become highly influential in current fashion photography largely through celebration of Chinese gay sexuality. In the Southern Cone, Marcos Zimmerman’s “Desnudos sudamericanos” poses its subjects in the nude against the backdrop of their daily life and professions. Through Zimmerman’s lens, the parallel views that the male body should be seen either as a work of art or as the personification of the art of work merge and become one.

Bibliography

The coinage of the phrase “male gaze” and its definition are attributed to John Burger and Laura Mulvey.

Berger, J. (2008). Ways of seeing. Penguin Classics.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and other pleasures. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan.

Pictorialism’s depiction of the male body in the context of its dialogue with modernist art forms can be best exemplified by Edward Steichen’s “Rodin - The Thinker” (1902), a portrait of the celebrated sculptor alongside his own creation, one of the time period’s most visible representations of the male nude across any artistic medium.

Asen, R. (1998) Appreciation and desire: The male nude in the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe, Text and Performance Quarterly, 18:1, 50-62, DOI: 10.1080/10462939809366209

Conrad, S. (2021). Globalizing the Beautiful Body: Eugen Sandow, Bodybuilding, and the Ideal of Muscular Manliness at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Journal of World History 32(1), 95-125. doi:10.1353/jwh.2021.0005.

Del Val, W. (2020 December 4). “Now in Berlin (if not quite *on view*): “MASCULINITIES – Liberation Through Photography.” 032c. https://032c.com/magazine/masculinities-alona-pardo-wes-del-valhttps://032c.com/magazine/masculinities-alona-pardo-wes-del-val

Eklund, D. (2004). “The Pictures Generation.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pcgn/hd_pcgn.htm

Leffingwell, E. (2003). John coplans: Exposures. Art in America, 91(7)

Pardo, A. (2019, June 26). “Humanism, Magnum, and the Family of Man.” Magnum Photos. https://www.magnumphotos.com/arts-culture/society-arts-culture/humanism-magnum-family-of-man-alona-pardo-david-seymour-edward-steichen-henri-cartier-bresson-moma-new-york/

Steichen, E., Sandburg, C., & Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.). (1955). The family of man: The greatest photographic exhibition of all time, 503 pictures from 68 countries.

STILL, J. (2003). (Re)presenting Masculinities: Introduction to “Men’s Bodies.” Paragraph, 26(1/2), 1–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43263710

Teicher, J. (2016, February 6). “When Photography Wasn’t Art.” JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/when-photography-was-not-art/